'Language possesses resources which one has to sense as coming not only from within

oneself, but from outside, from the land itself, from the rivers, from the forests. And

also from those persons and those cultures that existed in that landscape and have left

their trace.' Wilson Harris in conversation with Michael Gilkes (The Uncompromising Imagination) |

|

The title of this homepage sums up three major aspects of Wilson Harris's writing: his philosophy of existence, his conception of man, and the central importance he ascribes in both art and society to the regenerating role of the imagination. Poet, novelist and essayist, of mixed Amerindian, European and African descent, now a British citizen, Wilson Harris is the author of twenty-two novels and two volumes of short stories, which he sees as so many instalments of a never-ending quest or 'unfinished genesis of the imagination'.

He was born on 24 March 1921 and educated at Queen's College, Georgetown, in what

was then British Guiana. He became a Government surveyor in the 1940s, leading many

expeditions into the interior to do mapping and geomorphological research. He has since then explained the effect this experience has had on his perception of landscape, 'its density, depth and

transparency,' as a living receptacle of vanished peoples including his own forgotten Amerindian antecedents. This was to stimulate his conception of the human personality as a cluster of inner

selves ('one is a multitude', Jonestown, 5) strangers or often ignored components, whether man's animal ancestry or affiliation with the divine, in other words, an ontology that transcends the limits of the merely human and shows some affinity with a pre-Columbian world view. Living in multi-racial Guyana was also to inspire his notion of cross-culturalism (as distinct from multi-culturalism) rooted in a heterogeneous, largely

unconscious 'mutuality' between cultures, a constellation of so-called primitive and so-called civilised cultures, in which similarities appear between a pre-Columbian and a pre-renaissance intuitive approach to existence before rationalism dominated the European mode of thought. Above all, his experience in the Guyanese interior was the seed of his original art of fiction, making him reject realism as inadequate to represent its complex, living, ever-changing landscapes as well as the depths of the human psyche. From his first essays

(Tradition, the Writer and Society, 1967), he associated realism with the rise of imperialism viewing it also as the equivalent in art of political as well as social convention and privilege and therefore unfit to express both the livingness of

a 'humanized' nature and the subterranean tradition of the Caribbean peoples,

long deemed 'historyless' but whose terrifying past of dismemberment, slavery and exile he recreates as a legacy that must

be 'digested' in order to envisage a hopeful future.

He was born on 24 March 1921 and educated at Queen's College, Georgetown, in what

was then British Guiana. He became a Government surveyor in the 1940s, leading many

expeditions into the interior to do mapping and geomorphological research. He has since then explained the effect this experience has had on his perception of landscape, 'its density, depth and

transparency,' as a living receptacle of vanished peoples including his own forgotten Amerindian antecedents. This was to stimulate his conception of the human personality as a cluster of inner

selves ('one is a multitude', Jonestown, 5) strangers or often ignored components, whether man's animal ancestry or affiliation with the divine, in other words, an ontology that transcends the limits of the merely human and shows some affinity with a pre-Columbian world view. Living in multi-racial Guyana was also to inspire his notion of cross-culturalism (as distinct from multi-culturalism) rooted in a heterogeneous, largely

unconscious 'mutuality' between cultures, a constellation of so-called primitive and so-called civilised cultures, in which similarities appear between a pre-Columbian and a pre-renaissance intuitive approach to existence before rationalism dominated the European mode of thought. Above all, his experience in the Guyanese interior was the seed of his original art of fiction, making him reject realism as inadequate to represent its complex, living, ever-changing landscapes as well as the depths of the human psyche. From his first essays

(Tradition, the Writer and Society, 1967), he associated realism with the rise of imperialism viewing it also as the equivalent in art of political as well as social convention and privilege and therefore unfit to express both the livingness of

a 'humanized' nature and the subterranean tradition of the Caribbean peoples,

long deemed 'historyless' but whose terrifying past of dismemberment, slavery and exile he recreates as a legacy that must

be 'digested' in order to envisage a hopeful future.

Harris emigrated to England in 1959 but the Guyanese landscape and history have remained his main source of inspiration in his interpretation of individual behaviour and of historical catastrophe on a universal scale, while the Caribbean experience of fragmentation informs a major feature in his narratives: the disruption (in a perfect symbiosis between form and content) of all absolutes, static situations, or one-sided attitudes, through a dislocation of linear narrative, time scheme and of the conventional logic of language, a dislocation which initiates the transformation of the characters' vision through what he calls 'convertible images,' often extraordinary protean, multi-layered metaphors. A fairly simple example of such dynamic imagery is to be found in Palace of the Peacock (1960), the first part of The Guyana Quartet and a quintessential recreation of the New World conquest as of all attempted expeditions into the Guyanese heartland. The sun metaphor, at first a symbol of absolute and destructive power represented by Donne, the leader of the expedition, shatters in the last part of the novel into a constellation of stars that become themselves the eyes of the peacock's tail, at once multiple personality and vision of the expeditionary crew evanescently united with their Amerindian victims.

Palace of the Peacock also adumbrates the three notions of dream, psyche and genesis that inform Harris's later narratives with greater complexity. The 'dreaming' reconstruction of the past arises from the joint agency of intuition, the unconscious and the imagination. It arouses the narrator's vision into layers of his psyche and the density of landscape, the 'womb of space', the creative reality of spatial self and land, i.e. the dual initial ground of the reconstruction:

'The map of the savannahs was a dream. The names Brazil and Guiana were colonial

conventions I had known from childhood. . . They were an actual stage, a presence,

however mythical they seemed to the universal and the spiritual eye. They were as

close to me as my ribs, the rivers and the flatland, the mountains and heartland I

intimately saw. I could not help cherishing my symbolic map, and my bodily prejudice

like a well-known room and house of superstition within which I dwelt. I saw this kingdom

of man turned into a colony and battleground of spirit, a priceless tempting jewel I dreamed

I possessed.' (1960 edition, p. 20)

'The map of the savannahs was a dream. The names Brazil and Guiana were colonial

conventions I had known from childhood. . . They were an actual stage, a presence,

however mythical they seemed to the universal and the spiritual eye. They were as

close to me as my ribs, the rivers and the flatland, the mountains and heartland I

intimately saw. I could not help cherishing my symbolic map, and my bodily prejudice

like a well-known room and house of superstition within which I dwelt. I saw this kingdom

of man turned into a colony and battleground of spirit, a priceless tempting jewel I dreamed

I possessed.' (1960 edition, p. 20)

The Guyana Quartet creates a composite picture of the various landscapes of Guyana and of its heterogeneous population while evoking the circumstances like indentureship and maroonage that led to the creation of diverse communities. The Far Journey of Oudin (1961), is set on the East-Indian rice plantations between the savannahs and the coast, and it is Oudin's illiterate wife, Beti, who nevertheless becomes an agent of change. As Harris said in an interview, 'so-called ordinary people are much more mysterious than we think, and that was one of the things I discovered in the crews that I used to take into the interior.' In The Whole Armour (1962), which takes place on a strip of land between bush and sea, Cristo, a young man wrongly accused of murder, agrees to atone for the violence and guilt of his community. In The Secret Ladder (1963), the land surveyor Fenwick and his crew chart the river Canje prior to the building of a dam that will flood the territory occupied by the descendants of runaway slaves. This confrontation between a cruel modern technology and a people forgotten and buried in the heartland awakens Fenwick's conscience to the significance of an ineradicable part of the Guyanese historical legacy.

Each of these novels points to the possibility of eroding the certainties that lock the protagonists in a rigid sense of self, and thus makes possible the dismantling a fixed order of things. As already suggested, the landscape is not merely the outer equivalent of an inner psychological space, the 'womb of space' or fertile setting in which the protagonist's quest and 'drama of consciousness' take place. Its essential livingness catalyzes the characters' progression towards self-realization, as in Heartland (1964), in which Stevenson, a government agent travelling alone in the jungle undergrowth, is gradually made aware of an evolutionary scale and dimensions of being he had previously ignored, as when 'snake and man and beast,' he frees himself from an imprisoning rock and crawls on, 'half-fish, half-reptile'. Stevenson's heartland experience, his disappearance into the unknown and the inconclusive ending of the novel, with its emphasis on process and change rather than a clearly defined objective, can be read as an epitome of the unfinished quest whereby the protagonist sheds his self-righteous complacency and acknowledges his individual responsibility for the violence and failure at all levels of human relationships.

In the next cycle of novels the characters further explore the condition of loss and apparent void that marked the beginnings of West Indian history. In The Eye of the Scarecrow (1965), which evokes the economic depression of the Twenties and the Guyana Strike in 1948, the narrator suffers 'a void in conventional memory' as a result of an accident. The protagonist of The Waiting Room (1967), Susan Forrestal, blind and deserted by her lover, finds herself in a physical and psychological void. Prudence, the heroine of Tumatumari (1968) suffers from a nervous breakdown after the death of her husband and the delivery of a stillborn child. In Ascent to Omai (1970) Victor explores the heartland in search of his lost father. These novels combine the recreation of a state of loss with the twofold possibility of emerging from such a state and creating a new kind of fiction, as indeed, for Harris, reality is a living text, while fiction is as 'real' as reality itself. When the narrator in the later novel Carnival writes Masters' 'biography of spirit', he feels 'possessed by lucid dreams that intermingled fact with imaginative truth' (First edition, p. 15). The narrator in The Eye of the Scarecrow who keeps re-living his past from different approaches, Susan and her lover re-living their affair through the author's editorship, Prudence re-creating Guyanese history from her own memories and her father's papers, and Victor writing a novel about his father's trial for setting fire to a factory, are all in search of a 'primordial species of fiction,' rooted in a nameless dimension or 'sunken areas of tradition,' while the fictional process itself aims at an imaginative 'conversion' of deprivation which, in realistic fiction, often finds an outlet in self-righteous protest only.

Myth also plays a major part in bringing to light the regenerative capacity of catastrophe. From his earliest poetry and fiction, Harris has re-written both European and Caribbean myths, which in their modified versions become themselves mediating instruments between 'partial systems,' diversified expressions or multiple masks of an unattainable wholeness. The stories in The Sleepers of Roraima (1970) and The Age of the Rainmakers (1971) are re-interpretations of Amerindian myths, legends and historical incidents. They form an essential link between the earlier and the later fiction, especially the story 'Yurokon' which illustrates Harris's further exploration of cross-culturalism through the bone-flute metaphor, the instrument carved by Yurokon's Carib ancestors from their cannibalized Spanish enemies to penetrate their mind and intuit the kind of attack they would launch. The Caribs saw in the bone-flute the very origin of music. The bone-flute was therefore 'the seed of an intimate revelation . . . of mutual spaces they shared with the enemy . . . within which to visualize the rhythm of [their] strategy.' Since destruction (cannibalism) and creation (music) come together in the instrument, Harris expresses, through the bone-flute metaphor, his conviction that 'adversarial contexts' (the encounter of inimical cultures) can generate creativity. The bone-flute is also associated with the rhythm or 'music' which structures Harris's narratives, notably in Palace of the Peacock (see Author's Note in the 1998 edition).

Harris's approach to creativeness is further modulated in the subsequent novels, informed by an inner movement towards 'otherness', though he is also careful to show that the deprived 'other' can become possessive in turn. We see this in Black Marsden (1972), set in Edinburgh but a novel which also bridges continents, like the following ones as their characters travel imaginatively between the U.K. and the Americas or India, as in The Angel at the Gate (1982). Moreover, these narratives ceaselessly elaborate a bridge between the unconscious and what Harris calls 'the miracle of consciousness'. Clive Goodrich comes upon Black Marsden in Dunfermline Abbey and brings him to his house together with his agents, characters in their own right but also part of Goodrich's tabula rasa theatre, who threaten to impinge on his freedom of judgement and behaviour. Goodrich and Marsden reappear in Companions of the Day and Night (1975), set in Mexico, which initiates what Harris called at one stage 'the novel as painting,' a concept developed from 'convertible images' and particularly substantialized in Da Silva da Silva's Cultivated Wilderness (1977) and The Tree of the Sun (1978). Da Silva, the protagonist in these two novels, reborn from disasters and death in Palace of the Peacock and Heartland, is a painter who prepares his canvases for an exhibition and is stimulated to a profound re-vision of the experiences they evoke. In The Tree of the Sun the painter and his wife come across an unfinished book and letters which the former tenants of their flat wrote to each other but never sent. Da Silva's editing of this material is the subject both of the novel and his canvases. In most of his fictions, especially Palace of the Peacock and from the Da Silva novels onwards, Harris elicits correspondences between various forms of art, writing, music, painting and sculpture. For instance, in The Four Banks of the River of Space, Anselm, 'engineer, sculptor, painter, architect, composer', experiences at some stage 'a glimmering apprehension of the magic of creative nature, the life of sculpture, the genesis of art, the being of music' (First edition, p. 39).

The Da Silva narratives evince a superb rendering of the spirit of the places portrayed and of the nature of their civilization as well as an increased sensuousness. They are more specifically about the nature of creativity also foregrounded in the dialogue between author/editor and the creative protagonists in the Carnival Trilogy (Carnival, 1985; The Infinite Rehearsal, 1987; The Four Banks of the River of Space, 1990), in which the metaphorical writing blends with metaphysical, abstract reflexion (the association of 'vision and idea' in Palace of the Peacock). The three novels 're-write' Western masterpieces and suggest that, however admirable, the world view they present has become obsolete and may endanger the future of humanity. Carnival is a 'divine comedy of existence' in which, under the guidance of his Virgil, Everyman Masters (a name which blends his dual role as plantation overseer in Guyana, then as an exploited worker in a London factory), Jonathan Weyl explores the living conditions in the colonial Inferno of Masters's youth but also, like Dante, the possibilities of a spiritual rebirth. Unlike Dante, however, he does not move towards the eternal but discovers that the Inferno, Purgatorio and Paradiso can be transformed into fluid, overlapping states, parts of the endlessly changing, self-renewing existential process. Throughout Harris's fiction, the carnival metaphor stands, among other things, for endless creativity, the emergence into being under different, partial masks or social faces of formerly eclipsed, invisible West Indians (or faceless humanity generally), whose experience has nevertheless accumulated in the 'unattainable wholeness' (residues and legacies of experience and unconscious forces) mentioned above, also associated with the sacred. Carnival also involves the inverse process of a penetration of masks, not towards absolute Truth but towards many partial truths.

In the early novel The Eye of the Scarecrow the narrator comments as follows on his imaginative recreation of the past: 'It was to prove the re-living of all my life again and again as if I were a ghost returning to the same place (which was always different) shoring up different ruins (which were always the same)' (25). This statement foreshadows The Infinite Rehearsal, a phrase which sums up Harris's view of existence and his writing process as a repeated 're-vision' of reality from different angles and with a growing consciousness. The novel by that title is a 're-writing' of Goethe's Faust and to a lesser extent of Marlowe's Dr.Faustus, which brings to mind their present-day emulators. The protagonist's guide here is a character named Ghost (a 'spectre of wholeness') who helps him revise the past 'from the ruled or apparently eclipsed side of humanity' (3) and does so 'in an infinite rehearsal of a play of the birth of history' (8). An important motivation behind men's actions is their incorrigible lust for eternity, an absolute and static infinity, which convinces them that they '[possess] a duty to maim or kill in upholding the laws of God' (49). Whereas Robin Redbreast Glass's 'infinite rehearsal' excludes stasis and involves him in a ceaseless transformative movement of opposites towards each other: conquerors and victims or, for that matter, an alternative movement in the existential process between death and resurrection, darkness and light. The shifts in this novel between past, present and future announce a similar approach to time inspired by the Maya in The Four Banks of the River of Space and Jonestown (1996), the narrative in both novels weaving a cross-cultural bridge between a pre-Columbian perception of the universe and that of modern Western science. The plot of Four Banks 're-writes' The Odyssey with English and Guyanese characters. It disrupts and reverses the finality of Ulysses' deeds, particularly his urge to punish his enemies when he comes home, animated by jealousy and an implacable vengefulness, which have become a threat to civilization and the very existence of humanity when imitated in modern technological societies. Within the protagonist's inner, 'dreaming' reconstruction of the past, Ulysses' personality is fragmented into a number of actors who share the burden of his strong personality and become partial selves susceptible to a conversion to compassion and forgiveness.

Conversion is one aspect of the resurrection, another major theme which runs through Harris's work from the very beginning and is particularly developed in the Da Silva novels, taking on variable forms from one fiction to another: it can be the paradoxical presence of life in death; the emergence on the characters' consciousness of a previously ignored individual or historical past; the reappearance of characters, like Da Silva and Hope, who had disappeared or died in earlier narratives, though still involved in the existential process. More specifically, in Resurrection at Sorrow Hill (1993), it takes the form of a schizophrenic but eventually regenerating impersonation of figures like Montezuma, DaVinci and Socrates by the inmates of an asylum. However, the resurrection for Harris is never a final conquest of death. It is, to use his own expression, 'unfinished genesis' and therefore endless process.

Sorrow Hill, an actual location near Bartica in Guyana, appears in several earlier novels from Palace of the Peacock to The Eye of the Scarecrow and Genesis of the Clowns (1977). Many expeditions from pre-Columbian times to the present day foundered there. Its marginality on the world map together with the countless people who disappeared in the area make it the symbolical burial ground of a forgotten, often victimized, voiceless humanity. Similarly in Jonestown, the relation of a real massacre ordered by the American sect leader Jim Jones, who forced about 1,000 of his followers to drink cyanide soup or be shot on the spot, an obscure Guyanese location like the Jonestown settlement and the victims of the killings evoke the disappearance of peoples in Central and South America as well as twentieth-century holocausts and genocides. However, Sorrow Hill (and the Guyanese heartland, perilous object of so much covetousness) is described as 'an epitaph and a cradle' (Resurrection, 4), an oxymoron which sums up Harris's paradoxical vision of existence (death-in-life and life-in-death) and of creativity.

In all his novels Harris's major concern is to explore imaginatively uncharted territory (as he did the concrete landscape as a surveyor), to trace a subterranean tradition that grew out of the unacknowledged experience of all who disappeared into the dividing gulfs between peoples and cultures, into the 'gaps and holes' of recorded history. In parallel with his fiction, he has written a considerable number of essays on the nature of colonialism and post-colonialism. Though largely influential on post-colonial criticism, they run counter to the setting up of a sense of deprivation, and hence protest, as the sole or main source of counter-action. Instead, he repeatedly emphasizes the role of the imagination as a major, constantly evolving agent of change. Also, as he has repeatedly explained, creativity is largely throwing 're-visionary' or 'transfigurative' bridges across chasms to bring to light 'involuntary associations' between closed worlds of race and culture, between a neglected or 'invisible' human experience and the all too visible reality enclosed in conventional and privileged frames whether in real life or fiction. Creativity is at once the resurrection of a faceless humanity and an awakening to its presence and meaning in both nature and the universal community:

'Cultures echoing many voices, many accents of the present and the past congregated, broke apart, congregated again under Sorrow Hill. Not only human accents and voices but the speech of ghosts within the whisper of rain and river, fire, light, shadow in the leaves of a tree borne by the hand of Timehri, the hand of God, upon an invisible branch, a visible branch of the tapestry of the age of wood, the age of rock and water and skyscape and riverscape.' (Resurrection at Sorrow Hill, 3-4)

It should be clear from the above that Harris delves ever more deeply into the unconscious through the dreaming process, the mainspring of creativity. In The Dark Jester (2001) the narrative emerges from the dream of an anonymous character, which recreates the encounter between the conquistador Pizarro and the last pre-conquest Inca, Atahualpa. But historical time is relativized, embedded into an evocation of mankind 'across ages' as well as located with other species into nature and the cosmos 'across times'. It is, as Harris often says, a fiction that transcends a merely human discourse. In his backward and forward reconstruction of historical events, the Dreamer dialogues with the Dark Jester, a person who appears in Harris's early work as an artist who identifies 'with the submerged authority of dispossessed peoples'. In his essays Harris has often drawn attention to the limitations of Cartesian logic and its anthropocentric interpretation of the world, contrasting it with a phenomenal legacy and a tradition perceptible still in pre-Columbian art and which implies, as he says, 'a treaty of sensibility between human presence on this planet and the animal kingdom'. It manifests itself in the Inca iconography, the blending of human, animal and cosmic features in myths that inspire in the Dreaming narrator a poetic 'Atahualpan form' as opposed to the 'Cartesian form'. In this novel Harris also 're-writes' a Homeric myth by drawing a parallel between the Greeks' entry into Troy in a wooden horse and Pizarro's entry in Cajamarca, his wooden heart blind and indifferent to the hospitality he receives.

All through the narrative, the Dreamer attempts to answer related questions whose conception may have an impact on the future of humanity: 'What is History?, 'What is art?', 'What is prophecy?'

These questions also haunt the artist protagonist in Harris's last novel, The Mask of the Beggar (2003), and take him even further in his self-reflexive pursuit of a multi-dimensional art in a journey towards the roots of consciousness. As he makes clear in an opening note:

In The Mask of the Beggar a nameless artist seeks mutualities between cultures. He seeks cross-cultural realities that would reverse a dominant code exercised now, or to be exercised in the future, by an individual state whose values are apparently universal. He senses great dangers for humanity in this determined and one-sided notion of universality. He senses unconscious pressures within neglected areas of the Imagination that may erupt into violence. The roots of consciousness are his pursuit in a quantum cross-cultural art that brings challenges and unexpected far-reaching, subtly fruitful consequences.

In his excellent review-article of the novel, the writer Zulfikar Ghose points out that the narrative takes place in 'visionary Time', "time that is fugitive and trapped, fluid and stagnant" (CONTEXT N┬░ 14). At one stage, the artist expresses a 'confession', actually a summing up of the conception of art which, from his first novel on, structures Harris's own fictional sequence: the paramount role of intuition in the creation of a 'community of being' as reciprocal process and the capacity for change it could entail if applied in society. The artist's last thoughts are largely a meditation on the nature of art in general and of Harris's in particular. He does not idealize art but while defining his own aesthetics and intuitive approach to fiction, he criticizes a purely materialistic and technological civilization and the kind of fiction that fails to probe the deeper motivations and emotions which threaten mankind when they run berserk. This is counterpointed by his perception of both outer and inner spiritual life, of human existence interwoven with all elements in the universe, of a bridge between cultures inherent in what he calls 'cross-cultural psyche'. It informs the manifold imageries that orchestrate a multi-levelled, dynamic reality which, ideally, one should grasp comprehensively.

Zulfikar Ghose writes that Harris's fiction 'should be read like poetry . . . not subjected to a rational accounting that would convert moments of revelatory insight into some commonplace of mysticism. . . . Eliot said of Dante that we can only point to him and remain silent. I believe this is also true of Harris.'

Last updated in May 2004 by Hena Maes-Jelinek

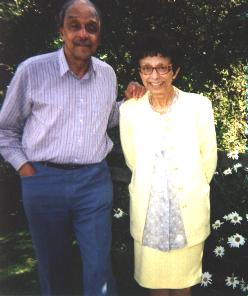

With Hena Maes-Jelinek

August 1998

|

Page hosted by the University of Li├Ęge

|

|